MIT Sloan Professor Relishes Role as a UROP Mentor

Basima Tewfik, who studies impostor syndrome, honored by students for her guidance and commitment to undergraduate research

Joey Davis and Laurel Kinman: A Multidimensional Collaboration

Biology professor's support inspires PhD student and protein enthusiast to prioritize mentorship in her career

Engineers, Express Yourselves

The MIT School of Engineering Communication Lab, which turned 10 in 2023, helps students translate their work for broader impact

Mentorship in Action Across Campus

MIT's vice president for Resource Development talks about MIT’s robust mentoring landscape and how alumni and friends can play a part

Passing the Baton of Science

Hologic-funded Jay A. Stein Professorship of Biology celebrates MIT innovation across generations

A Trusted Guide Can Make All the Difference

MIT President Sally Kornbluth on mentorship

Legacy of Student Art in East Campus

Before East Campus closed in summer 2023 for renovations, a project to digitally preserve some of the most beloved student art got underway

Spotlight On: Mentorship

Your Friendly Neighborhood Mentors at MIT

Resident Peer Mentor program formalizes the peer support that has always been a hallmark of residential culture at the Institute

Designing Effective Applications

MIT graduate architecture students offer guidance to potential applicants from underrepresented groups

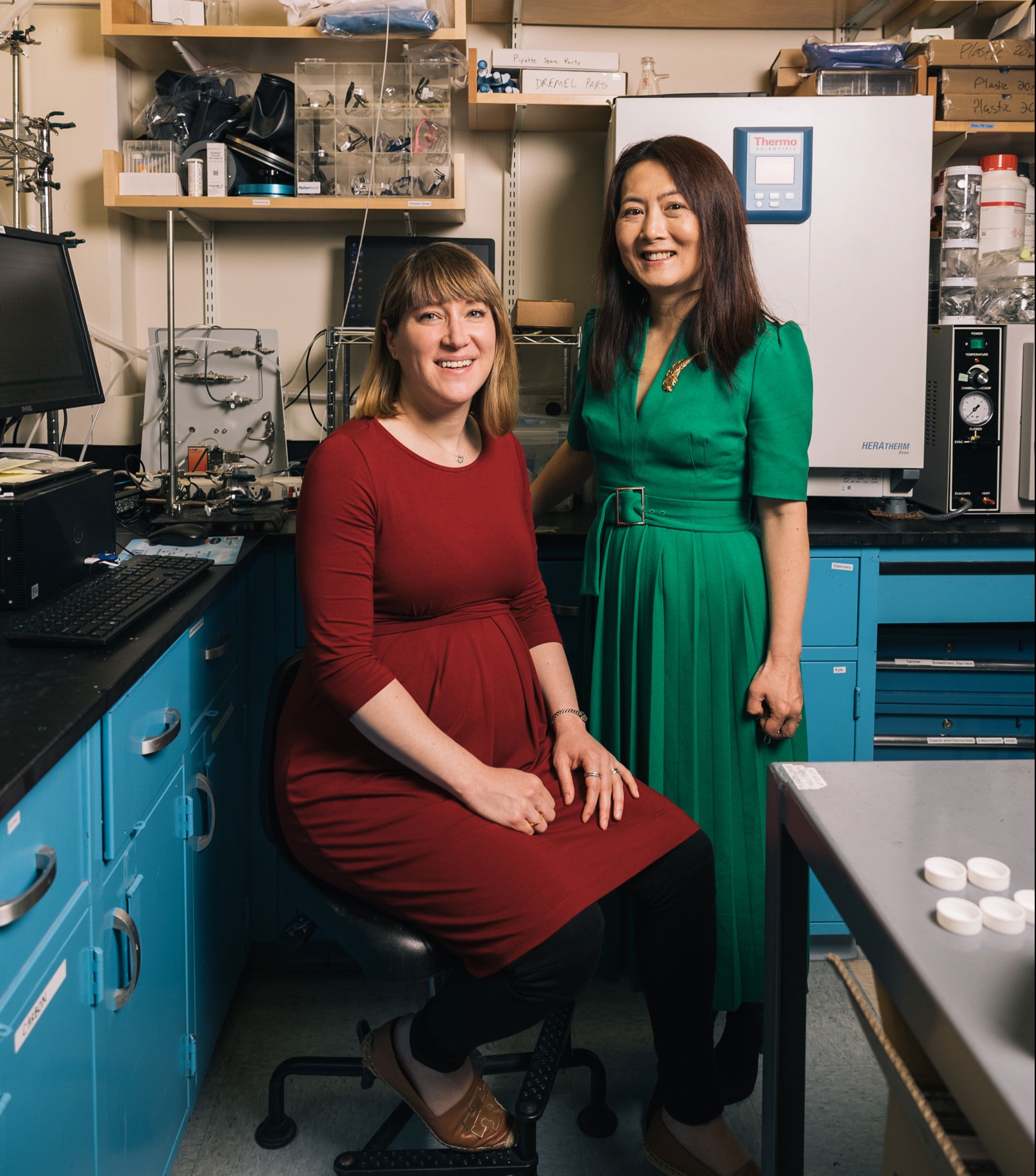

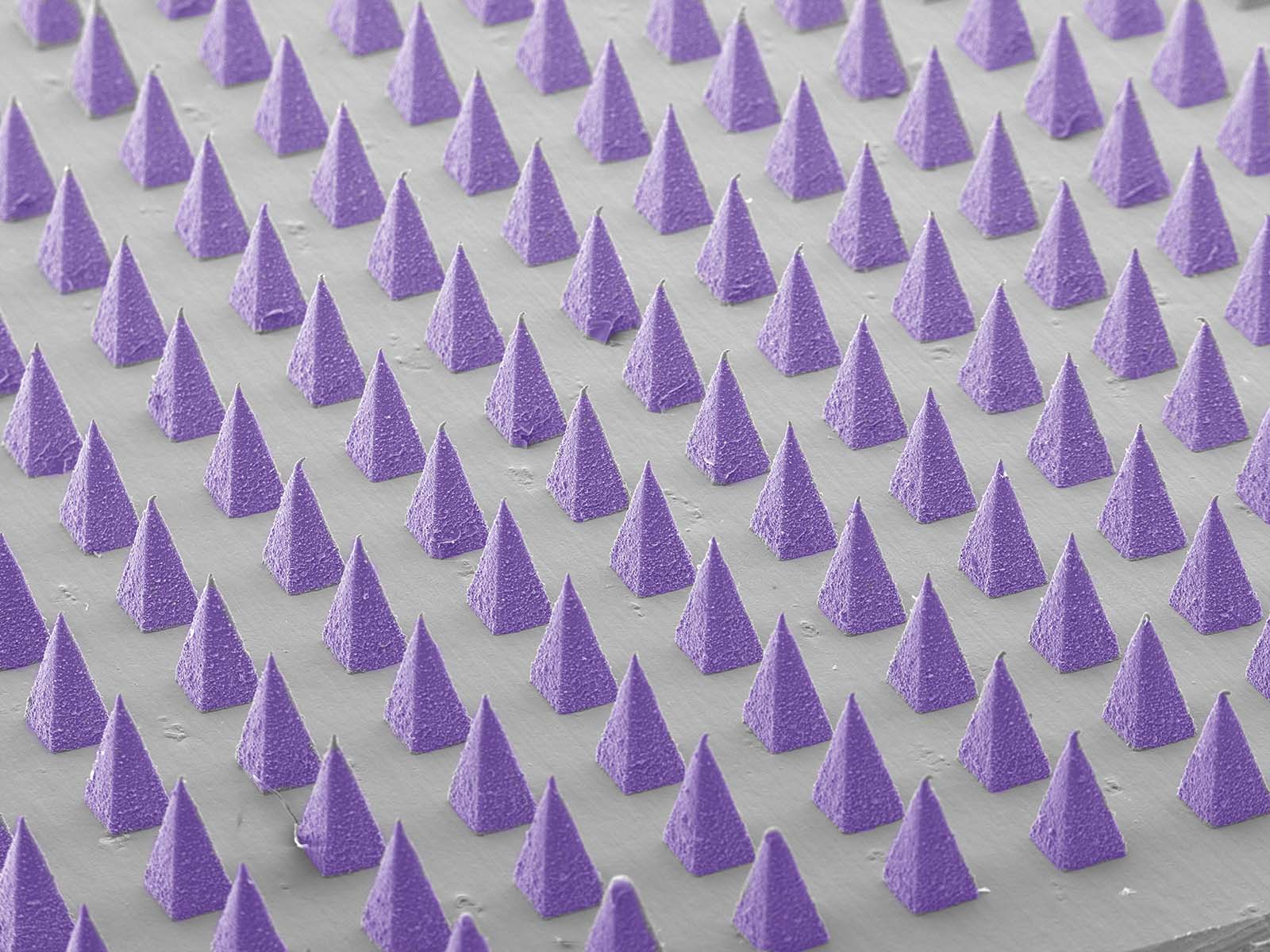

Yang Shao-Horn and Betar Gallant Have Positive Energy

Collaboration with Professor Shao-Horn, who works to uncover materials for next-generation batteries, cultivated Associate Professor Gallant’s intellectual potential

MIT programs provide a mentorship-paved pathway to doctoral degrees—and a potential launch pad to academia

Popular

When Movements Topple Dictators

Associate professor of political science Mai Hassan examines contentious politics and collective action in autocratic regimes—and the barriers to democratization that follow

Francesca Riccio-Ackerman Works to Improve Access to Prosthetics

PhD student is designing and building a sustainable care and delivery model in Sierra Leone

Three years of project work yield NEET students an experimental model of the human gut—and preparation for their postgraduation goals

MIT Bridge Project Spans Disciplines for Better Cancer Diagnostics

Researchers meld their expertise in engineering, immunology, and polymer chemistry to tackle ovarian cancer